Most startups plan like they're doing taxes—pessimistically and under duress.

"What can we do with the money we have and the time we've got?" They inventory their constraints, squint at their runway, and inch forward like they're defusing a bomb. It's logical. It's responsible. It's also how you build something aggressively mediocre that nobody particularly wants.

The best companies flip this script entirely. They start at the end and work backwards.

The Art of Reverse Engineering Dreams

Backcasting is beautifully simple: define a desirable future, then reverse-engineer the steps to get there. It's direction-setting, not fantasy planning. Instead of asking "What's necessary?" you ask "What's possible?"

The difference is everything.

Consider Peter Attia, who's turned longevity into performance art. He doesn't start his health planning with "What can I squeeze into my Tuesday?" He starts with a vivid picture of himself at 100: cognitively sharp, physically capable, probably still correcting people on Twitter. Then he works backward to design the daily habits that make that vision inevitable.

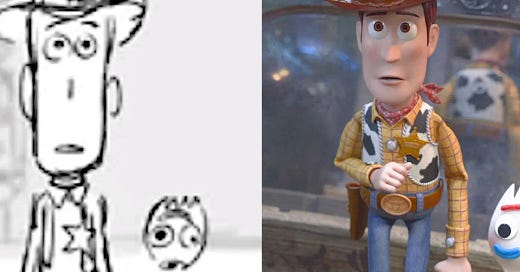

Pixar literally starts each film by defining the emotional "money shot"—the single moment that will make the entire movie worth watching. For Inside Out, it was Joy realizing that Riley needs to feel sad sometimes. For Toy Story 3, it was Andy choosing to give up his toys. They build entire narratives backwards from these moments. They don't guess what might work. They decide what should exist.

I do something similar with my own clients through what I call the "dream cover story" exercise. I have them write their fantasy headline—complete with publication name, specific metrics the journalist would cite, cultural impact quotes, and testimonials from thrilled customers. Suddenly, "I want to build something successful" becomes "TechCrunch: How [Company] Hit $50M ARR While Making Remote Work Actually Human Again." The vague becomes viscerally tangible. (And yes, they usually pick TechCrunch. I've stopped fighting it.)

Even Airbnb famously imagined an "11-star experience"—not because they intended to hire personal chefs and private jets for every guest, but because it stretched their imagination of what extraordinary could look like.

Why Forward-Thinking Founders Think Backwards

Here's what happens when you start from constraints: you optimize for survival instead of significance. You make defensible choices that feel smart in quarterly reviews but add up to something your own mother would struggle to explain at dinner parties.

Here's the thing most founders miss: backcasting isn't just planning—it's pre-writing your origin story. Every successful company eventually gets written about backwards ("How X saw the future before anyone else"), so you might as well design that narrative intentionally.

Backcasting flips your mental model. Instead of "What can we afford to try?" you ask "What would have to be true for this to matter?" It aligns your entire operation—brand, product, culture—around a shared vision that's actually worth reaching.

Your team starts prioritizing differently. Your storytelling gets sharper. Your decisions become more coherent because they're all serving the same North Star.

Most importantly? It gives you permission to think bigger than your current burn rate suggests you should.

"Isn't This Just Elaborate Daydreaming?"

Fair question. The line between visionary and delusional is approximately the width of a Post-it note when you're staring at your bank account.

But backcasting isn't about predicting the future—it's about designing one. You're not channeling Nostradamus. You're acting like an architect who sketches the finished building before ordering lumber.

The magic isn't in the vision itself. It's in the clarity that comes from having one. When you know where you're trying to go, every tactical decision becomes a question of whether it moves you closer or further away.

Your Turn to Start at the End

So here's the challenge: Stop planning from your constraints for a minute. Start planning from your conviction.

What does your company look like at peak impact? Not "successful" in some vague sense, but specifically, tangibly changing the world in a way that matters to you.

What will people say about you five years from now when they're explaining to their kids why your work mattered?

What has to be true between now and then? What’s holding you back from getting there today?

The answers might surprise you. They might scare you a little. And that's probably a good sign.

Because the companies that end up mattering don't start by asking what's realistic.

They start at the end.